Recently our artist Jonathan Dimmock has been giving many so many different concerts in such diverse musical roles that we thought it would be prudent to remind you that here at The Gothic Catalog, we know him mainly as an organist, and share some more information about his latest release with us, "Mendelssohn Organ Sonatas."

Mendelssohn’s six organ sonatas are not sonatas in the classical sense of that term, but rather a collection of pieces which he composed mostly between 1844 and 1845 - one year after his founding of the Leipzig Conservatory. Although we know that Mendelssohn made numerous corrections and changes to the first two editions which were published (Coventry, London and Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig), there are no indications of registration choices. In his “Prefatory Remarks” he says: Much depends in these Sonatas on the right choice of the Stops; however, as every Organ with which I am acquainted has its own peculiar mode of treatment in this respect, and as the same nominal combination does not produce exactly the same effect in different Instruments, I have given only a general indication of the kind of effect intended to be produced, without giving a precise List of the particular Stops to be used. By “Fortissimo” I intend to designate the Full Organ; by “Pianissimo” I generally mean a soft 8 foot Stop alone; by “Forte” the Great Organ, but without some of the most powerful Stops; by “Piano” some of the soft 8 foot Stops combined; and so forth. In the Pedal part, I should prefer throughout, even in the Pianissimo passages, the 8 foot and the 16 foot Stops united; except when the contrary is expressly specified; (see the 6th Sonata). It is therefore left to the judgment of the Performer, to mix the different Stops appropriately to the style of the various Pieces; advising him, however, to be careful that in combining the Stops belonging to two different sets of keys, the kind of tone in the one, should be distinguished from that in the other; but without forming too violent a contrast between the two distinct qualities of tone.

By the time these sonatas were composed, Mendelssohn was well-known as composer, pianist, and organist, having made many tours as a soloist throughout Germany and England. His improvisations were highly regarded; and it was while on tour in England that he was approached, by a publisher there, to compose some works for the organ. The 35 year old Mendelssohn may have wanted to impress his English colleagues, or perhaps even show them up, because he composed works with extremely virtuosic pedal parts, at a time in history when English organists had marginal pedal technique. Perhaps he wanted to assert his lineage to the great Bach tradition and the magnificent German organs which influenced his tonal pallette. Regardless, his masterworks for organ are justly regarded as the finest examples of Classical German organ literature.

These pieces are marked by two affects, strength and beauty. From the full and dramatic F minor chords of the opening sonata to the toccata-style final variation of “Vater unser im Himmelreich” (Sonata 6), it’s clear that this is intensely masculine, strong, technically demanding, and emotionally assertive music. Yet the magic of Mendelssohn’s pieces lies in his ability to play with light and shadow so convincingly. Assertiveness yields to lyricism and gentleness over and over again. In the midst of an angry opening section of Sonata 1, a simply-stated, soft chorale (“Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh’ allzeit”) enters to calm the storm. Slow movements of heart-rending beauty blend the yin and yang of his musical vocabulary as if he were touching our very soul.

It is this assimilation of the Romantic sentiment expressed within Classical and Baroque forms that makes this music so important to us today. The lineage from Bach to Mendelssohn is clear. But looking forward, we can also see how Mendelssohn’s Romantic side influenced the music of Schumann, Brahms, and Liszt. The organ, as an instrument, was undergoing tonal changes in the early nineteenth century; and it’s likely that Mendelssohn, as an international concert performer, and the students and colleagues he directly influenced (Richter, Gade, Becker, van Eyken) was the most significant force in establishing this change.

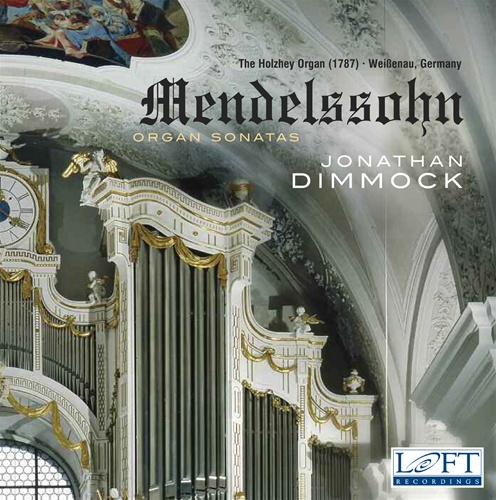

Notes on the Weißenau organ

Much has been said about Mendelssohn's penchant for Classically-voiced organs, his traditional leanings in his compositional style, and his conviction that Swell pedals were not necessary to convey the music of his organ pieces, yet the vast majority of Mendelssohn organ recordings ignore these points. This recording, however, highlights a Bavarian organ (a region Mendelssohn knew well), an organ builder that Mendelssohn praised (Holzhey), and a true Classical instrument placed in a stunning acoustical setting.

Often dwarfed by the fame of its large neighbor, the 1750 Gabler organ of Weingarten which is a mere five minutes drive from Weißenau, the 1787 organ in the Abbey church of Weißenau is undeservedly little-known. Three manuals and pedal in original condition, with many warm 8 foot flues, very supportive bass, and original strings and celestes, this organ has a unique and soothing tonal quality: strong without being strident, warm without being muddy, clear without being self-consciously bright. The temperament (Werkmeister III) was a slight challenge for some of the keys, but not insurmountable. And the advantages of an unequal temperament (standard for virtually all the organs Mendelssohn knew in Germany) for giving different tonal color to each key far outweigh the disadvantages. The trickiest aspect of the organ was the old pedal board. As is visible in the picture, the pedals could be more accurately described as "buttons" than as "keys." For Mendelssohn's extremely virtuosic pedal passages, this required some careful pedaling!

The Abbey church was founded in 1145 as a Premonstratensian monastery. Originally named "Weissenau" ("white meadow"), it is now a part of Ravensburg. The current church was built in the baroque style between 1708 and 1724. The monastery closed in 1802. Since 1283 Weißenau has been famous for its possession of the relic of the Precious Blood (referred to in "Lohengrin").

Check out everything Jonathan Dimmock is up to on his website

No comments:

Post a Comment