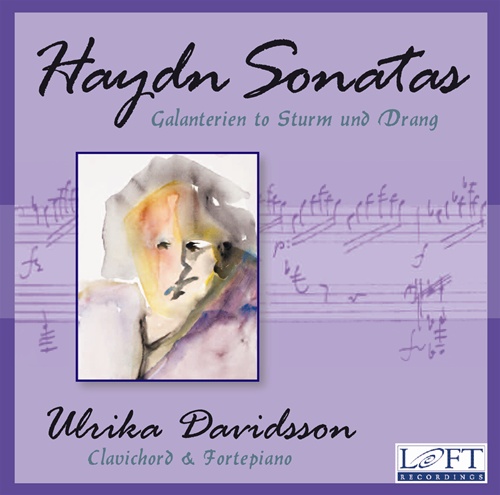

Earlier this year we released Ulrika Davidsson's album, Haydn Sonatas: Galanterien to Sturm und Drang, but today we wanted to tell you a little more about Haydn, Sturm und Drang, and some of the thoughts that have to go into a recording of this magnitude.

From Galanterien to Sturm und Drang

Franz Joseph Haydn’s large body of solo sonatas exceeds 60 in number, though some are lost, and the dates of their creation span more than 40 years. The earliest were written in his youth, in the early 1750s in Vienna, and the last were written in the span from 1791through 1795 during Haydn’s forays to London. There is great diversity in the material, technically and stylistically as well as musically, and they are recognized for their ingenuity and individuality. Every piece has its own set of figurations and its own motives and keyboard textures. Haydn seems to have had an endlessly flowing source of imagination and creativity when it came to exploring a variety of musical ideas. Regardless of the relative complexity of the pieces, Haydn managed to create music which entices the Kenner, or connoisseur, as well as it pleases the Liebhaber (amateur), and that incorporates the characteristic features of many styles, from the galant style, the Empfindsamkeit (the “sensitive style” of the late Baroque), and the Sturm und Drang (an emotional style full of “storm and stress”).

In the Baroque era, most pieces or movements of a larger work contained one single basic character, or Affekt. With the emergence of the galant style in the 1730s, rhetorical concepts still informed musical practice, but the music now expressed constantly changing moods and Affekts. Rather than general emotional states, such as joy, sadness, love, etc., the subjective and changing feelings of an individual (the composer) or of a programmatic idea were expressed. Contrast and variety became the norm. From the galant style, a more intensely expressive style emerged, the so-called Empfindsamer Stil (“highly sensitive style”). It could be expressed by frequent dynamic changes, large leaps, dissonant harmonies, and unexpected rests. Musical characteristics of this kind are well suited to express constantly changing and subjective moods. The foremost advocate for this style was C. P. E. Bach, and according to him, the instrument most suited to express these innermost feelings was the clavichord. (Haydn most likely owned a copy of Bach’s treatise Versuch über die Wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen.) He was also acquainted with some of C. P. E. Bach’s sonatas.

Sturm und Drang, a style which emerged in the 1770s, can be described as a more dramatic version of the Empfindsamkeit style. It was expressed by yet more abrupt changes, chromaticism, the use of minor keys, syncopations, and characteristic rhythms.

The keyboard works of Haydn incorporate the best of all these styles: the gallant, the Empfindsamkeit, and the Sturm und Drang. The various styles are reflected, in the music, by the increasing number of detailed directions for performance in the score, in terms of dynamic indications and articulation, as well as the overall change in texture and dramatic layout.

The “Shakespeare of music”

Haydn was praised for his musical rhetoric, and was referred to as “the Shakespeare of music.” Communication of the passions and the various sentiments in a piece was central to eighteenth-century thoughts on performance. A rich vocabulary of characteristic musical figures had developed, which were associated with various feelings and Affekts. They are usually referred to as “topics,” or subjects for musical discourse. Dances, with their various rhythms and other characteristics, were often used as such topics. A sturdy gavotte had different connotations than an elegant sarabande; a minuet referred to the courtly life, whereas a ländler (piece based on a folk tune) signified the lower social classes. Other “topics” Haydn frequently alluded to were the singing style; the brilliant style; the musette; the pastorale; the learned style or fugue versus galant style; Empfindsamkeit; Sturm und Drang; and the free fantasia. The connection between rhetoric and music was extensively discussed, for instance in the 1739 treatise Der Vollkommene Capellmeister (“The Perfected Chapelmaster”) by Johann Mattheson, a work we know that Haydn had in his library. Clarity of speech was of utmost importance, since a performance was often referred to as a musical declamation, and the musician as an orator and actor had to clearly communicate the character of the topics.

Character and tempo

The successful rendering of musical character depends on the choice of tempo. Various writers in the eighteenth century stressed that there are several factors one has to consider when choosing an appropriate tempo. The main issues are the meter, the tempo designation, the smallest note value, the harmonic pulse, and the Affekt or character of the movement. What we often call “tempo” designation is much more a “character” designation than an indicator of a specific tempo. For the player, the words adagio or allegretto give a sense of the character, or mood, and a feeling of physical movement (called Bewegung). The actual tempo that will suit a piece is then dependent on the interplay between the other factors mentioned. From this it follows that one allegro in 4/4 might have a very different actual tempo (as reflected in the numbers on a metronome) than another allegro in 4/4. The choice of tempo should not be the projection of a limited number of standard formulas or the projection of the performer’s spontaneous subjective preference, but rather a sensitive search for the balance of interacting compositional parameters inherent in each piece. The clue to the tempo is to be found in the piece itself, and its purpose is to render a musical character and its topics.

No comments:

Post a Comment