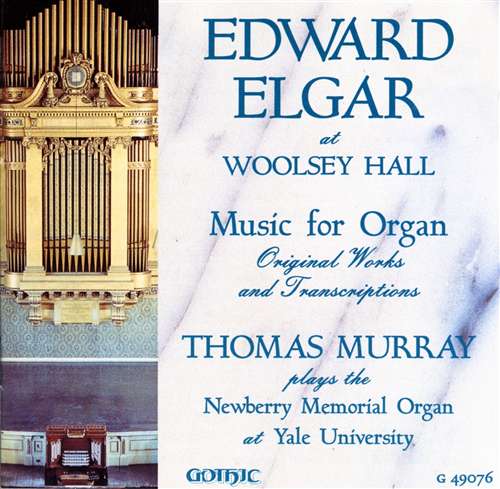

Edward Elgar at Woolsey Hall

Music for Organ

Original Works and Transcriptions

Thomas Murray, Organist

Newberry Memorial Organ at Yale University

- Imperial March, for orchestra, Op. 32

- Pieces (2) ("Chanson de matin" & "Chanson de nuit"), for violin & piano (later orchestrated), Op. 15 Chanson de Nuit

- Carillon, for reciter, organ & orchestra, Op. 75

- The Black Knight, cantata for chorus & orchestra, Op. 25 Solemn March

- Vesper Voluntaries (11), for organ, Op. 14

- Sonata for organ in G major, Op.28

Celebrate the occasion and buy today!

Choral Music of Edward Elgar

The Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, England

Richard Marlow, director

Richard Marlow's final recording as director of the Trinity Colleg echoir (Cambridge, England)! The choral works of Edward Elgar are gems of the English Romantic tradition. Under the direction of Marlow, the choir of Trinity College was the first mixed choir in a Cambridge college. As an adult mixed choir, they have the distinctive, clear English sound we admire, but with the power that only mature voices can produce. Highly recommended!

- Give unto the Lord, Op. 74 (1914)

- Ave Verum, Op. 2 No. 1

- Ave Maria, Op. 2, No. 2

- Ave maria stella , Op. 2, No. 3

- Light out of Darkness, Op. 29 (1896)

- Intende voci orationis meae, Op. 64 (1911)

- Goodmorrowe (1929)

- Te Deum, Op. 34, No. 1 (1897)

- Benedictus, Op. 34, No. 2

- I sing the Birth (1928)

- Doubt not, Op. 29 (1896)

- Fear not (1914)

- Light of the world, Op. 29 (1896)

- They are at rest (1909)

- Great is the Lord (Psalm 48), Op. 67

Celebrate and Buy Today!

While famous for his oratorios and cantatas, Edward Elgar is much less well known as an composer of sacred music than his contemporaries Charles Villiers Stanford and Charles Wood, or even C. Hubert H. Parry, whose works, such as the anthem “I was glad” and his Songs of Farewell have largely been appropriated for liturgical use (even though they were not written for church use). Elgar’s efforts in the sacred music genre tell an interesting and varied story. His early sacred works reflect his occupation as organist of St. George’s Roman Catholic Church in Worcester in the 1880s. As his fame as a composer became mainstream, however, his works for the church were shaped largely by the demands of Anglicanism, the English choral festival, and by the needs of publishers such as Novello, whose catalog mirrored Britain’s insatiable appetite for choral music at that time.

Elgar’s employment at St. George’s yielded a number of liturgical works. The three Latin miniatures of Op. 2, included here—Ave verum, Ave Maria, and Ave maris stella—were originally sketched in the 1880s; Ave verum began life as a setting of the Pie Jesu text from the Requiem Mass and was rewritten in 1902. The other two, also revisited later by the composer, were published in 1907. All three, eminently “High Victorian” in atmosphere, suggest the influence of John Stainer (whose Crucifixion was published in 1887), though there are periodic individual harmonic thumbprints and melodic turns of phrase.

It was not until the 1890s that Elgar and his music began to be noticed. After performances of The Black Knight (Worcester, 1893) and Scenes from the Bavarian Highlands (Worcester, 1896) as well as the publication of an impressive organ sonata (1895), he was commissioned by the Worcester Three Choirs Festival for an hour-long oratorio. The resulting work for that festival—Lux Christi (“The Light of Life”), Op. 29—is based on the story of the blind man restored to sight in the Gospel of St. John. Dedicated to the organist Charles Swinnerton Heap, it was first performed in Worcester Cathedral on September 10, 1896, and revised in 1899.

Three of the five principal choruses are included on this recording. “Light out of darkness” is an effusive acclamation of Jesus as “Saviour of the World”; “Doubt not thy Father’s care” is a reflective, intermezzo-like duet for sopranos and altos on Jesus’ healing of the blind man; and “Light of the World,” the most substantial and symphonic, occurs at the oratorio’s conclusion affirming Christ’s promise of eternal life.

Hot on the heels of “The Light of Life” were the Te Deum and Benedictus, Op. 34, commissioned by George Robertson Sinclair, organist of Hereford Cathedral, for the Hereford Three Choirs Festival of 1897. Both movements, thoroughly symphonic in conception (Elgar’s treatment of voices is palpably instrumental), reveal a new muscularity in terms of their pronounced melodic appoggiaturas and the potent admixture of diatonicism and chromaticism (probably gleaned in part from Parry and Richard Wagner). In fact the composer himself sensed that there was something novel, even radical, in this work which, with its contrapuntal integration of voices and accompaniment, looked to a new, progressive style of choral work.

It was during the Edwardian and early Georgians eras that Elgar reached his creative apogee. Between 1901 and 1914 he completed his greatest choral and orchestral works and, much admired by Hans Richter and Richard Strauss among others, enjoyed an international reputation. In replacing Parry as the nation’s unofficial composer-laureate, he also provided music for state occasions. For his solemn setting of “They are at rest,” an anthem written for the anniversary of Queen Victoria’s death and sung at the Mausoleum at Frogmore on 22 January 1910, Elgar drew on Cardinal John Henry Newman’s poem “Waiting for the morning,” a moving meditation from the Cardinal’s Verses on Various Occasions. The following year, in addition to his Coronation March, Elgar produced Intende voci orationis meae (“O hearken thou”), Op. 64, an offertory motet for the coronation of George V at Westminster Abbey. Subdued and devotional in tone, the harmonic language of this passionate miniature, with its unusual cadences, chromatic intensity (redolent of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde) and yearning choral gestures, reveals a new complexity in Elgar’s style which had been steadily emerging in the symphonies and the Violin Concerto.

“O hearken thou,” which used lines from Psalm 5, was one of three works of this period for which Elgar drew on the psalms. “Great is the Lord,” Op. 67, a larger, multi-sectional anthem, is a setting of Psalm 48 and was written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the Royal Society. In the outer sections it is possible to hear echoes of the finale of the Violin Concerto (“mount Zion on the sides of the north”) while the inner sections seem to draw more extensively on the motifsfirst heard in The Apostles and The Kingdom (notably the Allegro section and the bass solo). On a similar scale, “Give unto the Lord,” Op. 74, a setting of Psalm 29, was composed for the Festival of the Sons of the Clergy at St. Paul’s Cathedral where it was first sung on 30 April 1914 under the direction of its dedicatee, Sir George Martin, organist of the cathedral. In this work, features of Elgar’s style seem at their most pronounced. Much of the musical fabric is constructed by means of sequence imbued with the composer’s propensity for expressive appoggiaturas (such as during “Worship the Lord in the beauty of holiness”) and three-part counterpoint, while his love of modality lends a pensive melancholy to the more restrained central paragraph (“In His temple”).

Though conforming to a more traditional choral style (rather than the more “orchestral” one favored by Elgar in his larger works), the simpler anthem “Fear not, O Land” derives much of its appeal from unexpected changes of key (such as those in the opening fourteen bars), and Elgar’s dramatic return to the tonic (“do yield their strength”) is a particularly fine moment. Two other small gems, “I sing the Birth” and “Good Morrow,” date from the late 1920s. The carol “I sing the Birth,” a setting of Ben Jonson’s text (“An hymn on the Nativity of my Saviour”), was completed on 30 October 1928 and first performed at the Royal Albert Hall by the Royal Choral Society under the direction of Malcolm Sargent. An unusual conception, the piece begins with a modal alleluia (textually added by Elgar) which proceeds to intersperse monodic passages for tenor, alto, and bass before the whole choir engages in a full, four-part harmonization (the effect of which is both impressive and deeply emotional). This entire process is repeated as if to emphasize the prayerful simplicity of the setting, though the closing alleluias, which invoke the harmonic intensity of the Violin Concerto’s slow movement, have a more complex enigmatic quality in their conclusion on the dominant. “Good Morrow’” (this was its published title, though Elgar requested that the final page of the copy make George Gascoigne’s original sixteenth-century text available – as “Goode Morrowe”), described as “a simple carol for His Majesty’s happy recovery,” was written at the request of Sir Walford Davies (at that time organist of St. George’s Chapel, Windsor) to celebrate the recovery of King George V from serious illness. To supply this unexpected commission, Elgar went back to an old source of hymn tunes (just as he would do in 1930 for the Nursery Suite) which explains the uncomplicated, hymn-like manner of the regular phrases and stanzaic structure, though later verses reveal more elaborate textural treatment. “Good Morrow” was first sung by the choir of St. George’s at their annual concert in Windsor on 9 December 1929 under the composer’s direction; the performance was broadcast to the nation.

— Jeremy Dibble

No comments:

Post a Comment